The noise does not rise from palaces or parliaments. It seeps out of kitchens late at night, from taxi radios, comment threads, half-finished arguments between people who once trusted the system enough to ignore it. Populism does not arrive as theory. It arrives as a feeling, raw, impatient, and unmistakably human. Someone is finally saying out loud what has been muttered for years.

Populism gains strength where trust has thinned beyond repair. Institutions still function, elections still happen, laws still pass, yet something essential breaks. Representation feels ceremonial. Expertise sounds detached. Power appears to circulate among the same faces while ordinary life absorbs the consequences. Populism does not invent this resentment. It names it.

The appeal is immediate because it speaks plainly in a world saturated with hedging language. It draws villains sharply when systems blur responsibility. It offers emotional coherence where bureaucracy offers procedure. For those left bruised by economic shifts, cultural displacement, or political indifference, populism feels less like manipulation and more like recognition.

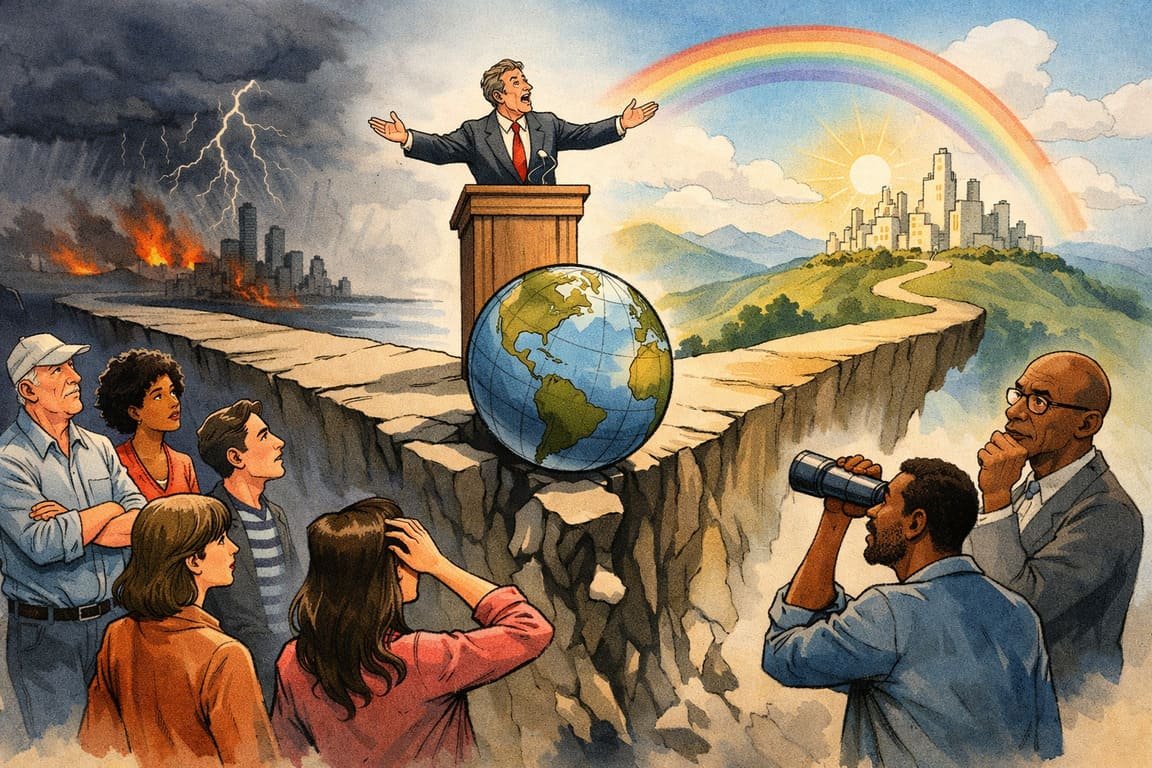

This is where many analyses stop, either celebrating the awakening or condemning the danger. Both reactions miss the tension at the heart of the phenomenon. Populism excels at diagnosis and falters at governance. Rage mobilizes quickly. Building institutions does not. The movement that thrives on disruption struggles with administration once power is achieved.

Democracy depends on a delicate balance between passion and restraint. Populism pushes hard against restraint, sometimes with justification. Without pressure, complacent systems decay. With too much pressure, guardrails bend. Minority protections weaken. Rules become negotiable. The voice of “the people” narrows until it sounds uncomfortably singular.

History repeats this rhythm with unnerving consistency. Populist waves surge when inequality widens and political language loses credibility. They recede when institutions adapt or when expectations collapse under the weight of reality. Rarely do they build durable systems alone. More often, they act as stress tests, revealing structural fatigue democracy preferred not to notice.

Supporters argue that populism revives participation, and they are right. Voters return. Debate sharpens. Apathy breaks. These are democratic goods. The danger lies in mistaking engagement for sustainability. Energy fueled purely by outrage burns hot and fast. Governing requires patience that anger rarely tolerates.

There is a narrative seduction at work. Populism simplifies complex systems into moral theater. Heroes and villains replace tradeoffs and constraints. That clarity comforts in uncertain times. Reality, however, resists reduction. When leadership clings to simplified stories, policy becomes performative. Consequences arrive uninvited.

Dismissal deepens the problem. Labeling populism as ignorance or extremism reinforces the very alienation that sustains it. Smarter democracies treat populism as feedback rather than infection. They ask what failed long before the shouting began. They respond without surrendering principle.

The most uncomfortable truth is that populism does not attack democracy from outside. It grows from democratic soil neglected over time. It reflects what happens when participation feels symbolic and power feels distant. In that sense, populism is neither cure nor disease. It is a symptom with sharp edges.

Late evenings in ordinary homes reveal its quiet origin. People are not plotting revolutions. They are trying to reconcile effort with outcome. They are asking why work feels harder while influence feels smaller. Populism gives that confusion a megaphone.

Democracy has survived noise, extremism, and even bad leaders. What it cannot survive is indifference. Populism’s greatest danger is not that it shouts too loudly, but that it exposes how few were listening before it arrived.

As the chants fade and ballots are counted, the deeper question refuses to settle: is populism seeking to replace democracy, or is it warning that democracy forgot who it was supposed to serve?